How to Avoid Making The College Essay A Battleground

Posted June 19, 2018, 12:00 pm by

The notorious college essay can become a battleground of underlying stress and tension for parents and teens. They both care about the outcome, but (or because of this) communication about it easily goes haywire.

Every parent-child relationship is different, and you have your own complex history that this post cannot address fully enough. Certain struggles, however, are common. From my years as a college-essay coach, I offer these suggestions for effective intra-family communication to help you navigate the college essay writing process productively, skillfully and with your relationship intact. Teens and parents have said these made all the difference!

Why is the essay so important, anyway?

What’s the purpose of the college essay? It’s hard to know the best approach if you don’t understand what you’re approaching.

Simply put, the college personal essay is personal – it’s all about high school students having a chance in their own voices to say, “This is who I am (right now), here are some of my most important qualities and values, and this is what is matters to me! And here’s a story that shows it!”

Many parents are aware this essay should, no pressure, be some of the best writing their kid has ever done. Why? Because suddenly it’s not just about a good English grade. It’s about impressing someone who has never met you and making them want you at their school. Parents mean well and want to suggest topics, direction or edits, sometimes at every turn. This can be a source of conflict. But more importantly, it can interfere with the student’s true task and necessary self-exploration.

An essay that winds up being an inauthentic version of what the student wants it to say based on what a parent wants it to say, is not the point at all.

How parents can constructively engage with college essays

These suggestions will help you stay on point and be more at ease.

1. Talk about the essay early.

Why not talk about the writing process with your student now? This summer? Before you’re caught up in it? Talk candidly, at a relaxed moment. Review together the purpose of the essay (for the applicant to share something meaningful not represented elsewhere in the application), and what kinds of things your student might feel moved to write about (it could change).

Ask questions such as, “What do you think will be the hardest parts of writing the essay for you, and how can we deal with that? What kind of support from me would feel good? What feels like too much, what too little?” (Most of the parents I work with have the “too much” problem!)

2. Let the teen lead.

Honor the student’s growing need for independence. For better or worse, it must be the student’s voice that is heard in the essay and throughout the college application. Ask directly: “How much do you want me involved, and in what way?” Or,“If you end up needing help but don’t want it from me, where can you get it?”

3. Be Reflective.

Take a little time to think about your relationship to your child, and how you’ve reacted to their habits around high-stakes products thus far. Can you honor your teen’s need for autonomy in the essay? If not, why? What are your needs, and are those needs objectively reasonable? What are you most stressed about, or anticipating as the biggest hurdles in the writing process? Can you see your teen as an evolving individual? If you feel brave, and ready for an honest answer, you could ask your teen directly, “How much do you think I see who you really are?”

4. State your needs as yours.

When you state your needs, label them as yours. Not more important or urgent than your teen’s needs, but yours. For example, “I need to know you won’t miss the deadline for the supplemental essays while you are thinking about the main essay, because otherwise I can’t sleep at night.” Or, “I need you to update me on your writing progress once each week.” Try to keep your needs related to responsibilities that are non-negotiable, like due dates. If you need to vent your stress, do it elsewhere.

5. Ask your student to ask for what they need from you.

It would really help you to know this directly and specifically! Most teens are able to say what kind of parental help will be best, for example, “I would love your help with punctuation,” or “Do you think I described the robotics program fully enough?” (And remember, there are some things they just CANNOT HEAR FROM US!). If you think your student needs further help, suggest where to find it.

(And note to students: Assume that your parent wants this essay to be really strong, but may be unfamiliar with the genre. See suggestion No. 1! Give your parent the benefit of the doubt in wanting to help you the best way possible. Parents are stressed and can’t control the outcome, either. Try to give them specific, reasonable ways to support you. )

6. (Re)Remember what the essay is for.

Once the essay is written, if your teen shares the essay or the topic with you, you may have very strong or sensitive feelings about it. It may seem reasonable to say, “I need you not to write about my breast cancer, that’s nobody’s business outside our family!” But remember, students are writing about something that was a big deal to them, that reveals their characters, something that changed them, so why not this? What parts of themselves will they get to explore and show by writing about a family illness? And that’s what you could (re-remember to) ask about: “If it’s really important to you to write about my cancer, what will you be showing about yourself?” This redirects the conversation and concern to being sure the student is meeting the essay’s purpose.

Your student might be unwilling to write the essay they want to write at the risk of losing your approval or affection. And that could lead to resentment or bad feelings.

7. Show your ongoing but noninvasive interest.

Tell your teen something like, “If you’d like to share your writing at any point, or your feelings about it, I’m just going to listen, I’m not going to respond unless you want me to. Would you like me to? Let me know.”

Or ask about the big picture, what the teen wants to convey in the essay, to help focus and sharpen the writing. This is also a way of saying, I care about your perspective and helping you do what is asked of you.

Anytime your teen seems lost or seeks your input, you could try asking: “What personal quality does this essay show that might not be demonstrated in your grades, your scores, your transcript? How are you showing that to colleges, and where? Why is that important to you?” Exploring these questions deepens your relationship with your teen and, if answered well, makes sure the essay fulfills its purpose.

These are stock, judgment-free questions (we use them with all our college applicants who come for help!).

Or, if the teen (still!) doesn’t have a topic, you could ask: “What do you value most about yourself? What do you struggle with the most? How will this school help you with that? What story can you use to show that?”

8. Show solidarity.

Most parents won’t try this, but I REALLY recommend it! When a teen feels like a parent is nagging, a common response is: “You have NO IDEA what I am going through!” And your student might be right.

To develop empathy, and a sense of exactly what is so hard about writing the college essay, try writing one yourself (you can use one of the Common App prompts). You’ll see pretty quickly why the struggle may be about more than “just sitting down and writing it.” It’s hard to write about yourself, but what a rich learning experience! Push yourself to see what you can produce, especially if you don’t consider yourself a writer.

Offer to share your work with your teen, who is taking a big step in trusting you (and the world) by sharing writing with you. I really really urge you to give it a try. Doing so can increase your compassion and appreciation for your teen’s efforts and struggles.

9. Listen and ask.

Be an active but neutral and nonjudgmental listener. If your teen has shared some writing with you, even for the second, third, fourth time, always ask, “Do you want to hear what I think?”

If your student says, “No,” ask if there would be a better time to try again. If your teen insists, “No,” try to let it go, and go share your opinion with the mirror, or the dog or your partner.

If your teen says “Yes,” deliver your feedback as neutrally and nonjudgmentally as possible.

For example, if you can’t really understand the story, try something like, “I see you’ve chosen a topic you’re really passionate about, but I’m having a hard time following what’s going on in your story. Could you try telling it to me out loud another way?”

LISTEN to their answer, and repeat it back so the teen can hear it. As a writer, sometimes it’s most helpful simply to state what you’re trying to do out loud to a friendly ear.

If these ways of communicating are new for you, practice the following suggestions out loud first so you sound natural when addressing your teen.

-

Done!? If your teen says the essay is “done,” don’t balk at their crappy grammar but try asking, “Have you read it aloud slowly to check for mistakes?” Even if you feel under-equipped or unsure how to help them with those issues, there is someone who can and the teen can improve essays a lot just by proofreading slowly aloud! By reading to you, your teen also has a chance to listen to the story freshly, and might just hear where improvements could be made. And all you’ve done is sit there, full present!

-

Approval and Affection: Always offer your approval in advance, approval for who your teen is at heart, their ability to make good choices, and to pull this off. And offer feedback as your perspective only, not The Truth. Practice saying something like, “You know I love you however this turns out, and whatever you choose to write about. I trust you, and I’d love to continue to be included to whatever degree you want me involved.”Say this to yourself until it is true. Do not say it to your student until you mean it 100 percent (teen BS detectors are so strong!). If you can’t quite get there, say whatever part of it you are sure that you mean. “You know I love you…” or “You know I love you however this turns out.” Whatever face you might see, your teen is under stress.

-

Praise and cherish your teen for whatever IS accomplished. Even the most discontented teens tend to know well what they didn’t do. They are often their own best critics. So, however hard it may be, praise what’s been done, and let love come before criticism.

We do not critique newborns for how they get born; we just love them for exactly the limited little creatures they are, doing their best. That quality – being a person just trying to figure out how it all works – is still in your teen (and in each of us!), and it will be good for both of you to see it.

Blog Categories

- Career Advice

- College Admissions

- Colleges & Universities

- Financial Aid and Scholarships

- For Counselors

- For Parents

- For Students

- Gap Years

- Mental Health and Wellness

- Online Learning

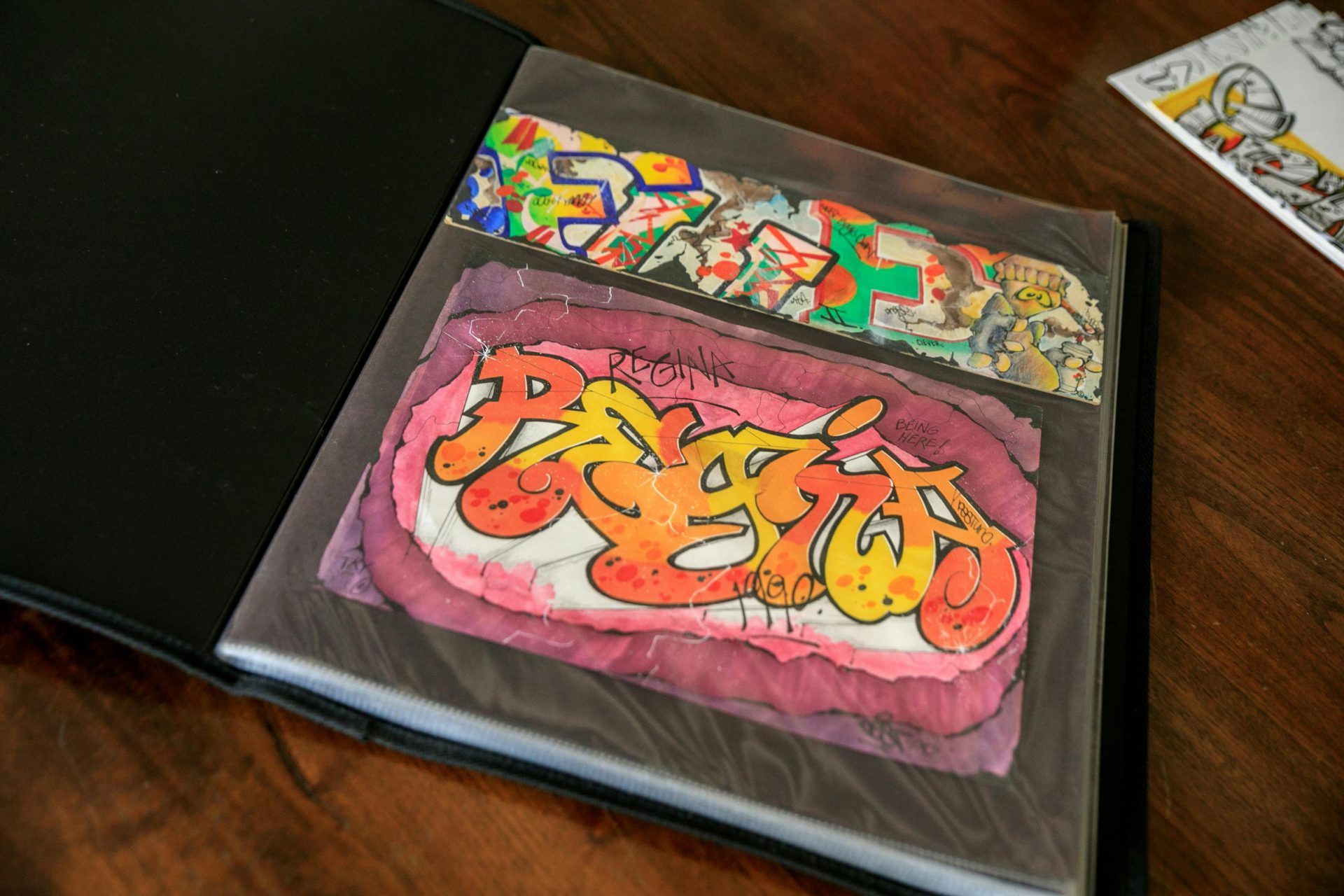

- Performing and Visual Arts

- STEM Majors and More

- Summer Programs

- Teen Volunteering

- Trade & Vocational Schools

- Tutoring & Test Prep

Organization with listings on TeenLife? Login here

Register for Free

We’re here to help you find your best-fit teen-centered academic and enrichment opportunities.

Forgot Password

"*" indicates required fields